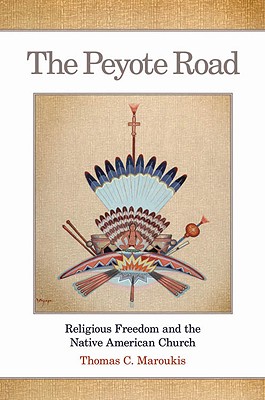

Originally published by the University of Oklahoma Press in 2010, the paperback edition of ‘The Peyote Road: Religious Freedom and the Native American Church’ by Thomas C. Maroukis came out in 2012. Maroukis, Professor of History at Capital University, Columbus, Ohio, has previously written ‘Peyote and the Yankton Sioux: The Life and Times of Sam Necklace’ (2004).

The peyote cactus grows in limestone soils and is scattered between the Rio Grande In southern Texas and north-central Mexico, largely in the Chihuahuan Desert region. Its use in Mesoamerica can be archeologically traced back as far as 5000 BCE, with various works of rock art depicting its ritualistic use— especially in a context with deer and rain. A wide variety of cultures apparently made use of it. With the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors in 1519, the Aztec empire that was still making use of peyote soon crumbled. The Roman Catholic Church, with the infamous Inquisition, arrived soon after to cultural redefine the peoples of Mesoamerica and their religions; part of which was the victimization of plant use as the ‘work of the devil’. A well-tested approach that had been employed in the European witch-hunts.

Within the ancient context, however, the North American Indian tribes did not traditionally use peyote. While it continued in isolated areas of Mexico, Maroukis traces its expansion into northern territories through tribal dissemination during the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. At the same time, the United States Federal government was employing a policy not far removed from that of the Spanish conquistadors, as they attempted to herd together and ‘Americanize’ the Indians. This ‘cultural genocide’ took on many forms, which included the creation of reservations, the creation of boarding schools to educate young Indians in a Western manner, legislation banning their traditional dance rituals, and, as it came to prominence, attempts to make peyote illegal. However, in many respects, as they destroyed the community of the tribes, they actually lent credence to peyote as a community-serving activity that solidified their cultural identity—aiding its dissemination.

Not all American Indians backed Peyotism, but while many did not join the Way and retained traditional or Christian beliefs, others actively protested against it (interestingly, Peyotists are welcome to hold multiple beliefs as every individual must find their own path to the same end.) Those individuals opposed, though respecting their own ‘traditional’ heritage, believed that the way forward was in a pan-Indian tribalism and an Americanized future. This group largely centred around the Society of American Indians, founded in 1911, in Columbus, Ohio. A Yankton Sioux called Gertrude Simmons Bonnin (1876-1938) was particularly outspoken and became a figure something akin to Harry Anslinger (the infamous anti-cannabis official). However, while Peyotism was very far from universal in the early Twentieth Century, it did steadily increase.

“In addition to Peyote as medicine, the Peyote faith offers its followers and potential followers a moral code and an ethical way of living, All Peyotists believe that Peyote is a teacher and that it is the basis for one’s ethical standards. Peyote teaches a way of life; it gives one a path to follow, the so-called Peyote Road” (Maroukis 2012, 87)

According to Maroukis, there are three major factors that helped Peyotism spread amongst the reservations in Oklahoma and into other parts of the United States and Canada. Firstly, is that Peyote is considered a “medicine” with the power to heal; secondly, cosmologically speaking, elements of the faith parallel traditional beliefs and practices; and thirdly, Peyote was considered a teacher that teaches one an ethical way of life—the Peyote Road. What are called Roadmen travel between reservations holding prayer meetings. However, these should not be considered as shaman or priests. They make the point that it is Peyote itself that is the teacher and the Roadmen merely facilitate its Way. There are two major types of ceremony that occur; the Half Moon Way and the Cross Fire Way. Although there are some differences in the alter they use, and different degrees of Christian elements, the role of Peyote itself is universal.

It is the legal battles between Indians, States and the Federal government that lay at the heart of Maroukis’ narrative. He expertly tells the story about the evolution of the Peyotist’s legal strategy, which is both eye-opening and, at the same time, rather disturbing (that such fierce, bias and ignorant opposition should have been in existence.) In fact, in many respects, it is a story that shares many elements with other pharmacographical histories, so far as oppressive state policy, combined with zealous, single-minded individuals who trade on hearsay and misinformation, combine to victimise a certain minority group. After reading, one is left feeling rather angry. However, while such battles, on different fronts, occurred over the Twentieth Century, the Peyotists quickly took a very wise step. In 1918, in Oklahoma, they incorporated as the Native American Church in order to lobby for first amendment rights with Peyote as a central sacrament. Other groups followed until the Native American Church of the United States was founded in 1944 (it later became ‘of North America’.) Not only did this place them within the legal constructs, thereby allowing them a floor from which to debate, but it also gave them strength in numbers.

One of the major strengths of this book are the detailed accounts of ceremonies, discussions over the meaning, value, and symbology of the objects that are involved in rituals, and how they work within a larger cosmological framework. One really begins to get a feel of how the Peyotists have a distinct form of ritual—one in which the central sacrament plays an integral role. In many respects it is a one-sided narrative, in which Peyotists seem unable to put a foot wrong (although, for all I know, this could be the case) but in the face of such bureaucratic vitriol over the existence this was perhaps a wise manoeuvre—as was the downplay of the visionary aspects of the plant in the book. However, as a broad history of the use of Peyote in North America, how it is culturally employed, with what meanings and functions it performs, the book is invaluable and very informative.

Validate your login

Sign In

Create New Account